Good From Far

“Swedish-Canadian Lars Cuzner is a trickster who you’re never sure is on the level. Using assumed identities and provocative language, his work has often sparked controversy, addressing uncomfortable topics such as racism, Nordic nationalism and the rise of right-wing populism all over Europe. As part of the festival’s ongoing Situation Reports, he roamed the streets as a self proclaimed “con-artist” interviewing politicians and the general public attempting to raise funds for his self help book that he describes as a ´really bad book.´” Forbes.com

Lars Cuzner’s “Good From Far” is about artistic research and literary production. This three-year endeavor aimed to explore the boundaries of publishing, authorship, and the commodification of ideas in the contemporary literary landscape.

The primary objective was to secure a book deal with a publisher without presenting any written content.

This is an excerpt from a terrible book, Good From Far, by me, Lars Cuzner.

It was never meant to be a good book and I lied to get it published. Actually, that’s not entirely true, I told people that I was lying, but I wasn’t. If you can’t get people to believe you, tell them you’re lying. So I told everyone that I’m a con artist. They didn’t believe me because I’m a conceptual artist. It’s a simple enough trick, which is a good thing, because in the confidence game, simplicity is your best friend.

The art scene, or the so called international contemporary art scene, to be exact, has internalised and accepted a set of social behaviours that in other areas of life would be considered scams. What this means is that in the arts, you can apply manipulation techniques that are used in straight up illegal cons without it being considered criminal. To understand this we need to look at the complex relationship the art profession has to insecurity.

Exactly no one is surprised to hear that cons are prevalent in the art world and I will explain why that is, but this book is not an exposé of art world high finance. It’s not about forgeries or money laundering. That’s a real thing though, art money is a massive con and one of our societies most accepted unregulated economies. But that is for another story. This is a self help book that explains the psychology of the confidence and insecurity game. The art scene just happens to be the perfect place to illustrate this particular kind of game.

I’m going to teach you in this book is how to use your insecurity to your advantage. First you need to understand that most people with influence in the art field confuse cultural power with power. The professional art world focuses on describing struggles and conflicts that will never effect the art world, and those who represent it will most likely believe that they are agents of real change in society. To con someone you need to make them first con themselves, and that is much easier with people who are already self-delusional about something that is so obviously not true.

Back to the opening statement of this introduction. This is actually a poorly written book and I don’t want anyone to correct it. I’m not just saying that to be coy, I’m trying to prove that I pulled off my con. Call it professional pride. I got the publishing deal before I had written anything. I am not an author and I have never published anything. I got this book deal because I’m an artist and I said that I was a con artist. The only promise I made was that the book would be bad. Since I’m an artist people just assumed that I wasn’t telling the truth. I’m using the art world to get a self help book published. To make money, obviously. That should sounds counter-intuitive. Art is necessarily selective and self help isn’t considered much of an art form. To pull this off I had to do a con.

First of all, know this. The easiest people to con are people who are highly educated and consider themselves intelligent. The reason for this is simple, they believe themselves to be above being duped. The perfect mark. The art profession attracts this type of person in droves since it yields irrational levels of social status. And because it’s a very small and competitive field, both in number of jobs and audience, it is overrepresented with easy victims of easy scams.

Disclaimer: Throughout this book you might find yourself thinking -“That’s not only true for the art world. That’s true in any profession” – and you would be correct in thinking so, but there are some specific differences that set the art profession apart, so let’s start there.

In theory, the art game is a pretty easy scam, the problem is that everyone who is playing it is insecure. The confidence game thrives on insecurity, but when everyone in the game is disguising their own insecurity, they are more sensitive to micro expressions of over-playing your confidence. The art game is about fluid confidence while struggling. I know, it’s confusing, and it has to be played over several years. In the art world you have to fake being a little bit fucked up, or fake being poor. It’s about being interesting. Easy living makes for boring people and everyone knows it.

The scam is to pretend that you are insecure but successful. This is confusing for people who are actually insecure. Competition is fierce and it doesn’t take much to get a bad reputation. You are constantly being read. Intelligence agents do this, they call it butt sniffing, like dogs do. They are professional bullshitters so they sniff out bullshit on the first meeting with anyone. You know that old joke? “Deja moo – The feeling that you’ve heard this bullshit before”. My kids always loved this joke and used to say it to me whenever I started telling them how this new project was the one to get us out of this crappy apartment.

When you’re getting started, you don’t really know why your efforts aren’t paying off. You don’t know what you’re doing wrong, and when it does work you don’t know why it worked. You’re just winging it. Because that’s what you do in the beginning. Nobody is showing you what to do, and they don’t teach you this in school, (because, frankly, the truth isn’t very flattering). In this confidence game you have to learn to use your insecurity as a weapon. I tell this to young aspiring artists and I tell them what works – not what they think works – but what actually works. If they listen to me they enjoy it more and get better results, they survive the game longer. Naturally, most young people are not receptive to this kind of advice and bless them for that.

The Intelligence Party

“With Lars Cuzner’s project “The Intelligence Party”, 2018, they finally arrived at the topicality, because Lars Cuzner has set up a fictional party here with which he moves in Graz as if he were on an election campaign tour. Tirelessly, the committed artist introduces the program of his “Intelligence Party”, a party that on the one hand demands the humanist demand for a right to vote for foreigners, and on the other hand supports this demand with right-wing arguments, such as true love of the homeland. The paradox seems hardly to go – and yet: in talks around post-colonialism, for example, “nationalism as a legitimate anti-colonial resistance movement” (Varela / Dhawan) is repeatedly discussed. The fact that steirischer herbst artistically discusses contradictions like these in various forms, is exactly what makes it so necessary this year.”

All across Europe, the right fears what they call “the Great Replacement,” where eroding European values supposedly cannot hold up to Islamic fundamentalism… and worse. The Intelligence Party, initiated by artist and activist Lars Cuzner, has a proposal to assuage these fears. Founded in Norway, the Intelligence Party is named after one of that country’s oldest political parties, which was led by romantic poet Johan Sebastian Welhaven in the 1830s. Today this party is reborn and appeals to cultural protectionists across Europe to enshrine the most important right of all: the right to vote. The universality of this right and its constant expansion is the most quintessentially European value of all, the Intelligence Party argues, and it should therefore be extended to non-citizen residents, regardless of where they come from. The party’s thinking goes that universal participation in elections would reveal more commonalities than expected between European and non-European residents, who might, it would turn out, share with conservative electorates a concern for family values, religious freedom, and the protection of cultural identity. That, at least, would stop any fundamentalist insurgency in its tracks, so the Intelligence Party proclaims. After spreading the party’s message in Norway and several other European countries, online, and in rousing public discussions, Cuzner now turns to Austria and Graz. Paradoxically injecting a left-wing demand into a right-wing agenda and presenting it to an undecided electorate, Cuzner and his party question today’s hackneyed notions of politics as well as the truth-procedures used to reach them.

You can read Lars Cuzner’s text “The Great Replacement” in this book.

“More absurdly, this technique is used by the artist Lars Cuzner in the project Intelligence Party – the conservative traditionalist party, in which the artist nominates his candidacy for the European Parliament. Here is the image of the artist: Lars, with a lush red beard, in a woolen three-piece suit, with a cane, comes out of a shiny white old fashion car to talk with voters and hand out caps with official symbols, slogans in the spirit of “I understand white people” or “All women are stupid” and the election campaign demanding universal suffrage.”

Aroundart.org

European Attraction Limited Tours

Press release

For their first exhibition in France, Lars Cuzner and Cassius Fadlabi have formulated a specific artistic proposal that resonates with current social events and questions the ethical engagement of artists within civil society. Together, they create improbable projects that take the form of installations associated with media events. For LE CAP – Centre d’arts plastiques de Saint-Fons, they present an installation titled European Attraction Ltd Tours, which features a film of a refugee camp shot from a helicopter. The installation as a whole is a continuation of a project initiated in 2014 in Oslo, focusing on the notion of the “human zoo.”

Borrowing their mode of communication from mass media, they create a provocative work that questions the role of the image, as well as the civic and ethical responsibilities of the artist in society and the impact of their actions in the context of real-world issues.

European Attraction Limited began in 2014 in Oslo. On the occasion of the bicentennial of the Norwegian Constitution, Lars Cuzner and Cassius Fadlabi recreated a human zoo, Kongolandsbyen, originally built in 1914 by a leisure company named European Attraction Limited to celebrate the centennial of the Constitution. Beyond critiquing a culture of colonialism, the project also implicates the audience: its appetite for voyeurism and its taste for scandal.

European Attraction Ltd Tours in 2017 addresses another facet of the human park, now resonating with contemporary European geopolitical issues: refugee camps. The film produced for the exhibition at LE CAP – Centre d’arts plastiques de Saint-Fons critiques the obscene gaze that the media invites us to cast upon the other. Confronted with others and their pain (Susan Sontag), we Europeans are often so ill-equipped that we prefer to add filters, barriers, images, rather than face the reality. Worse still, the camp becomes a tourist zone that one can fly over without confronting any danger.

Cassius Fadlabi & Lars Cuzner, European Attraction Limited tours, 2017. Couresty: Artists and LE Cap-Centre d’arts plastiques de Saint-Fons

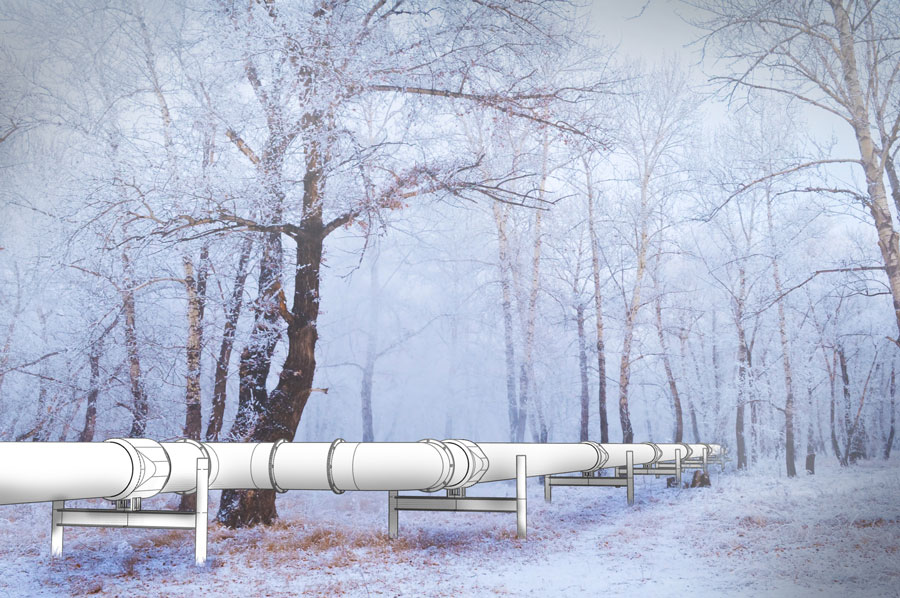

Milk Pipeline

An oil pipeline transporting milk from Norway to Russia.

Arsenal, The National Center for Contemporary Art, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia

MILK PIPELINE by Cuzner and Fadlabi

Milk running through an oil pipeline from Tana in Northern Norway to the National Center for Contemporary Art in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia.

A project about the objectification of national identities through subsidised consumption. Subsidised milk bars. Milk entered mass consumption as the symbol for the new welfare state, a new kind of homogenised and easily digestible socialism.

The focal point of the exhibition will be the space of the bar, a relatively new type of location for interpersonal exchange in the context of Post-Soviet Russia. Capitalist production makes us constantly choose and purchase identities, and the space of the bar is one of the most important sites for that process, at once inviting and impersonal. So, a lot of pieces in the show will reference the rituals of meeting and conversing. The art will serve as an objectification or unmasking of the unregulated emotional, friendly or hostile exchanges that make up the social communion. Other artworks will address various states of social policy that regulates exchange – the Socialist past, the capitalist present and the plans for a fairer future.

The Milk Pipeline-Milk Bar that opened July 15th started a couple of years ago when Valentin Diaconov invited me and Fadlabi to exhibit Scandinavian social democracy in the National Centre for Contemporary Art, inside the Kremlin, in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia.

It’s a long story, however, we ended up having to send a shipping container filled with Norwegian milk to the Art Centre in Russia. Here’s part of that story.

Originally, our suggestion was to export Norwegian milk to Russia via an oil pipeline (real pipes that Statoil provided us with) ending up at a milk bar in the art centre, referring to the 1930’s milk propaganda milk-bars in Sweden. Milk was at the time going through some major advanceus allowing everyone in the country to drink the exact same milk with the exact same taste and quality. The country was also in the process of adopting the new welfare state and milk would conveniently be used as the perfect representative symbol for the new system. The whole country could be unified, strong, healthy and, in the prime of scientific racism, white (something Sweden was one of the world leaders of at the time).

Now, we are not living in Sweden and our pipeline was to begin in our newly adopted country, Norway, Sweden also doesn’t share a border with Russia, Norway does. Norway was at the time of the milk propaganda era primarily concentrating its milk production for export purposes, and for a while, it was a strong export industry for Norway. But then came the oil. Even though fossil fuels is the Norwegian export product de jour, there is another export industry that Scandinavians excel at – the export of moral and ethical values based on its own perception of developmental superiority. So milk, marketed as an extension of the Scandinavian identity to this day, would still fit the bill. It is however illegal to export milk to Russia. An embargo that started in 2015. With all the arts money being thrown at the arctic regions right now the support as an art project was still feasible. There is a reason for this of course, white washing has turned into art washing. Statoil would, at the exact same time of our installation, be commencing the process of helping Russia and the USA with its oil explorations in the Arctic. In fact, they can’t do it without Norway’s help. However problematic this may sound, there was no cause for concern, because this whole project was understood as satire, and everyone knows that there is no weaker form of critique than satire. So we kept working.

The pipeline was very close to being realized, really fucking close actually. Statoil told us they would lend us real oil pipes for free, Tine Milk gave us permission to install the pipes at their dairy factory in Northern Norway, the National Art Centre in Russia was preparing on their en (at no small risk to the centre) and an award winning Danish/Norwegian film team was waiting for the green light. It would be one of the most ambitious art projects Norway had ever seen, and we had most of the puzzle pieces on the table.

Our project is a collaboration with Valentin Diaconov (Russia), the National Centre for Contemporary Art (Russia) and Henrik Underbjerg of Stray Dog Productions (Denmark). This is an export of the Scandinavian nature and values, transferred and delivered via pipeline from Norway to Russia. The milk will arrive at a milk bar and served to visitors at the exhibition FOOLPROOF FEELINGS at Arsenal in Nizhny Novgorod.

Artists: Yuriy Albert, Arman, Antonina Baever, Alexander Brodsky, Natalya Goncharova, Lise Dechen, Anya Zhelud, Junichiro Ishii, Lars Cuzner and Cassius Fadlabi, Natta Konysheva, Irina Korina, Cristian Krohn, Eileen Quinlan, Anna Lyalina, Paul McCartney, Matthieu Martin, Yasumasa Morimura, Tatyana Nasipova, Natalya Nesterova, Alexander Povzner, Dmitry Tugarinov, James Welling, Robert Falk, Jonas Čeponis, Cindy Sherman, Ilya Kitup, ZIP Artgroup.

European Attraction Limited

The human zoo, Kongolandsbyen, originally created in 1914 by the entertainment company European Attraction Limited, was rebuilt 100 years later by Fadlabi and Lars Cuzner.

Centred around the make up and build up of Scandinavian style superiority, it was a project that was done with a very literal reading of what the public is. During several years created in, and in large part, by the public, whatever direction that would take.

Lars Cuzner and Fadlabi’s project “European Attraction Limited” was an artistic endeavor that culminated in 2014 after a four-year research and development process. The project aimed to recreate and recontextualize “Kongolandsbyen” (The Congo Village) exhibition from Norway’s 1914 centennial celebration, which had displayed African individuals in a human zoo-like setting.

Research Process

The artists’ research began in 2010 when they discovered information about the 1914 exhibition. Surprised by the lack of public awareness surrounding this historical event, Cuzner and Fadlabi embarked on an extensive investigation into Norway’s colonial past and its implications for contemporary society.

Their four-year research process involved:

- Historical analysis of the 1914 exhibition

- Exploration of Norway’s role in colonialism

- Examination of collective memory and national identity

- Engagement with scholars, activists, and community members

- Development of artistic strategies to address sensitive historical material

Project Development

As the project evolved, Cuzner and Fadlabi faced numerous challenges:

- Ethical considerations regarding the recreation of a problematic historical event

- Balancing artistic expression with social responsibility

- Navigating public discourse and potential controversy

- Securing funding and institutional support

The artists aimed to use their project as a catalyst for public dialogue about racism, historical amnesia, and national identity in Norway.

Anti-climactic Opening

Despite the extensive research and preparation, the final unveiling of “European Attraction Limited” in 2014 was described as anti-climactic. This outcome can be attributed to several factors:

- Public controversy: The project generated significant debate and criticism before its opening, potentially overshadowing the actual event.

- Expectations vs. reality: The four-year buildup may have created unrealistic expectations among audiences and critics.

- Artistic interpretation: The artists’ approach to recreating the historical exhibition might have differed from public expectations.

- Contextual shifts: Changes in social and political discourse during the project’s development could have affected its reception.

- Curatorial decisions: The presentation and framing of the project may have influenced its impact on viewers.

The anti-climactic nature of the opening raises questions about the effectiveness of long-term artistic research projects in addressing complex historical and social issues. It also highlights the challenges of translating extensive research into impactful public art.

In conclusion, Cuzner and Fadlabi’s “European Attraction Limited” represents a significant attempt to confront Norway’s colonial history through art. While the project’s final presentation may have been perceived as anti-climactic, its four-year research process and the discussions it generated contribute to ongoing debates about historical memory, national identity, and the role of art in addressing societal issues.

The Original “Deep Fake”

The 1914 Congo Village exhibition in Norway can be understood as a form of historical “deep fake” for several reasons:

- Misrepresentation of origins: The exhibition purported to showcase Congolese people, but in reality, it featured individuals from Senegal. This deliberate misrepresentation was likely due to the difficulty of recruiting actual Congolese participants and the organizers’ assumption that the Norwegian public would not discern the difference.

- Colonial aspirations: Norway, despite not being a major colonial power, sought to project an image of participation in European colonial endeavors. The exhibition served as a means to align Norway with the broader European colonial narrative, despite its limited actual involvement.

- Constructed narrative: The village was a carefully curated representation of African life, designed to fit European preconceptions rather than accurately portraying the diverse cultures of either Congo or Senegal.

Reenactment Challenges

Cuzner and Fadlabi’s decision to reenact this problematic exhibition posed several challenges:

- Ethical considerations: How does one recreate a historically racist display without perpetuating harm?

- Authenticity vs. critique: The artists had to balance creating an authentic representation of the original exhibition with providing a critical framework for viewers.

- Contextual shifts: The meaning of such a display has changed dramatically between 1914 and 2014, requiring careful framing of the project.

Implications of Reenactment

The reenactment of this “deep fake” colonial display had several implications:

- Exposing historical fabrications: By recreating the exhibition, the artists highlighted the constructed nature of colonial narratives and Norway’s attempts to align itself with larger European powers.

- National identity examination: The project forced a reconsideration of Norway’s self-image as a nation without a colonial past.

- Questioning representation: The reenactment raised issues about who has the right to represent whom, and how historical misrepresentations can be addressed in contemporary art.

- Challenging collective memory: By bringing attention to this largely forgotten event, the project confronted Norway’s selective memory of its past.

Artistic Strategies

To address the complexities of reenacting a “deep fake” colonial exhibition, Cuzner and Fadlabi likely employed several strategies:

- Transparent framing: Clearly communicating the historical context and the problematic nature of the original exhibition.

- Critical engagement: Encouraging viewers to question the assumptions and power dynamics inherent in such displays.

- Collaborative approach: Potentially involving descendants of the original participants or contemporary African artists in the project’s development.

- Documentation and research: Emphasizing the four-year research process to provide a comprehensive understanding of the historical event and its implications.

The anti-climactic nature of the final presentation may have stemmed from the difficulty of translating these complex issues into a public art installation that could effectively communicate the layered meanings and critiques inherent in the project.

In conclusion, Cuzner and Fadlabi’s reenactment of the 1914 Congo Village served as a powerful tool for examining Norway’s relationship with colonialism, the construction of national identity, and the ongoing impact of historical misrepresentations. By recreating a “deep fake” from the past, the artists invited viewers to critically engage with both historical and contemporary issues of representation, power, and cultural identity.

100%

Expectation

Since most of you who are reading this and most of you who will see this piece of shit show also make unnecessary and useless art I might as well get right to it. At the time of writing this text I have no idea what this show will consist of or be about, but rest assure it will be an extraordinary aesthetic experience delivered by exceptional objects. Or not. Who cares? Probably not actually. I just found out that I am doing this show and it has to be ready in one week. Not only that, but the text has to be ready tonight. And it’s not like I have a studio filled with brilliant artworks just waiting to be exposed. In any case, your expectations are most likely unproportionately low or unproportionately high.

Modus Operandi

What is it about? Take your pick. It’s either about some psychological oddity that I read about in Cabinet magazine or some historical-political-unres

“Lars is a parasite that doesn’t actually do anything himself but gets noticed because he never leaves the party…”

from “Lars Cuzner’s Conversational Ghosts” by Kjetil Røed, 2014

Whatever Kjetil! The whole premise for this critique is based on something I supposedly said at some early morning after party. And saying that I don’t do anything myself is low – what do critics do if not exactly nothing themselves? Granted, bringing this up in a text for an exhibition might seem misplaced, but so is publishing personal attacks that rather than addressing the work simply critiques the lack thereof (and it’s not the first time he does this to me either). Just focus on the work, ok?

Fake Fight

Sure, I didn’t paint the painting; it’s by Leonard Rickhard and belongs to the Department of Cultural Affairs, as does the furniture. But I still had to do things myself to get it over here. Among other things, the wall colour had to match and it all had to be transported. Well, actually, I got lucky with the wall colour, they still had a bucket of the same paint at their office, and to be fair, Cultural Affairs did cover the whole transportation bit themselves, but that’s only because the work is very valuable and has to be transported with official Fine Art movers.

Forensics of Attraction

Lars Cuzner and Fadlabi’s project “Forensics of Attraction” at the 2013 Bergen Assembly represents a critical examination of the phenomenon of “human zoos” and the commodification of cultural otherness. This collaborative work was part of their ongoing project “European Attraction Limited” (2010-2014), which investigates historical instances of human exhibitions, particularly focusing on the 1914 World Fair in Oslo.

Conceptual Framework

The artists employed a “conspirative narrative” approach to expose the mechanisms of spectacle and viewer complicity in the context of cultural exploitation. Their work at the Bergen Assembly was situated within the “Institute of Imaginary States,” one of the fictitious research institutes that structured the exhibition. This conceptual framing allowed Cuzner and Fadlabi to explore the intersection of art, anthropology, and postcolonial discourse.

Methodology and Execution

As part of their research process, Cuzner and Fadlabi undertook what they described as a “pointless trip to Thailand” to investigate contemporary manifestations of human zoos. Their focus on the Paduang (Kayan) women, who have been displaced to tourist-oriented ethnic villages since the 1980s, drew parallels between historical human exhibitions and present-day cultural tourism. This approach underscored the persistence of exploitative practices in the guise of cultural exchange or preservation.

Critical Reception and Impact

The project generated diverse reactions, ranging from praise for its critical importance to accusations of pointlessness. This spectrum of responses highlights the controversial nature of the work and its success in provoking dialogue about the ethics of cultural representation and the legacy of colonial exhibitions.

Theoretical Implications

“Forensics of Attraction” can be situated within the broader context of postcolonial art practices that seek to deconstruct and critique historical narratives of cultural display. By focusing on both historical and contemporary examples of human zoos, Cuzner and Fadlabi’s work interrogates the continuity of exploitative practices and the complicity of viewers in perpetuating these systems.

In conclusion, Cuzner and Fadlabi’s project at the 2013 Bergen Assembly represents a significant contribution to the discourse on cultural representation, spectacle, and the ethics of display. By employing innovative research methodologies and presentation strategies, the artists effectively challenged viewers to confront the complex legacy of human exhibitions and their contemporary manifestations.

Share

Christian Sleep Over

My neighbours changed their wi-fi network name to STOP PLAYING SHITTY PIANO (in upper case). This was clearly directed at me since I’m pretty sure I’m the only one in the building who demonstratively can’t play the piano. But I persisted, feeling that I had been called upon through some divine intervention to learn contemporary Christian pop songs from Mega Chords. Mega Chords has the latest in Christian pop and rock, no doubt because religion is bigger today than ever.

This unprecedented emergence of religion in our times can also be detected in the vast amounts of nothing-believers who also doubt truth in evidence. Finding it hard to identify a Messiah for this nothingness you find yourself accepting conservative values inside structures that romanticize meaninglessness. This rejection of meaning is unsettling for you, and your fundamentalist belief in non-fundamentalism has you demanding revelations and importance only from that which you recognize as unimportant, something you feel is banal enough to escape purpose – like a Star Trek movie – where Spock recently re-popularized the phrase – “When you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” (which Trekkies will tell you comes from Sherlock Holmes, and Sherlockians will tell you comes from some other origin, but I don’t really feel like sitting here googling forever about things that only reinforce your thirst for post-purpose purpose).

As part of the curated residency program at 0047 during the summer we invite you to first resident initiated event.The Residency is mobilized by Goro Tronsmo and Kine Lillestrøm

The Conference

The two day conference European Attraction Limited attempted to put to the table a non-parochial view on the relevance of a proposed project to recreate a human zoo that occurred in Oslo in 1914.

Prior to the exhibition European Atraction Limited, art theorists and academics create a narrative around possible approaches to understand a project that had not yet been done. In May 2011 Fadlabi and Lars Cuzner received funding from KORO/URO to commence the three year project European Attraction Limited. The rebuilding of Kongolandsbyen from the 1914 world fair in Oslo.

Contributors:

Will Bradley, The Revolution Performed by the Workers Themselves

Elvira Dyangagani Ose, Historical Reenactment

Rikke Andreassen, Human Exhibitions. Race, Gender and Sexuality at the Turn of the Century

Tejumola Olaniyan, The Misconception of Modernity

Bambi Ceuppens, Whose Museum is it Anyway?

Walid al-Kubaisi, Racism Embedded In The System

Geir Haraldseth, The Terrible Beauty of Hindsight

Sandy Prita Meier, The Imaginary Other

Tobias Hübinette, Contemporary Racial Stereotypes in the Nordic Countries

Susan Buck-Morss, History as a Gift

Nina Witoszek, The Origins of the ‘Regime of Goodness’

Fatima El-Tayeb, Colour Blind Europe

-Salah Hassan, The Darkest Africa Syndrome: the Idea of Africa and its (Re)presentation

The Conference

Articles in Kunstkritikk (Norwegian) 1 2 (external links)

European Attraction

by Will Bradley

The challenge in thinking through Lars Cuzner and Mohamed Ali Fadlabi’s proposal to recreate the Congolese Village exhibit from Oslo’s 1914 centenary exhibition is to escape the straightforward statement that it seems to offer. This short text aims to reexamine the starting point, to question the ready-made terms of the debate, to look beyond the instant ideological meaning and break open the polarised imagery, in order to escape conclusions that otherwise might seem natural and obvious.

We should begin with the facts as they are recorded. London-based, Hungarian-born impressario Benno Singer was engaged by the Oslo 1914 exhibition committee to produce an amusement park as part of a large-scale outdoor international exhibition in Frogner Park celebrating the one hundred-year anniversary of the Norwegian constitution. The Congolese village was in turn part of Singer’s fairground, alongside a rollercoaster and a pantomime theatre among other attractions. Eighty people, apparently from the Congo (no certain confirmation of their country of origin has yet been found, but a visitor reported conversing with them in French), performed some version of their imagined daily life for the Oslo public in a setting built to resemble an ‘authentic’ African village. The reactions from the Norwegian press were overtly racist: ‘exceedingly funny’ wrote Norway’s newspaper of record, Aftenposten; ‘it’s wonderful that we are white!’ wrote a now-defunct magazine called Urd. But as an attraction the village was great success, and it was credited with drawing a significant part of the 1.4 million reported visitors to the exhibition.

Oslo was late when it came to staging an international exhibition, behind even Bergen which had held an International Fisheries Exhibition in 1898. The genre was, of course, pioneered in France, and in general was dedicated to showcasing the wealth accumulated through the two central methods of capitalist expansion, industrial organisation and colonisation. The Oslo exhibition was atypical in that it celebrated neither industry nor colonial expansion, but rather a political moment that must, in practice, have referred more directly to Norway’s recently-gained independence. Still, for reasons a future historian must elucidate in detail, it took the 19th century exhibition model as its blueprint, and so participated in the projection of a capitalist and colonialist state image modelled on that of its European neighbours.

The primary precursor to the Congolese Village in Oslo is the 1897 exhibition at the Brussels International Exhibition, which explicitly celebrated Belgium’s brutal African conquests; several of the 267 Conglese citizens transported to Brussels for the occasion died during the exhibition period, and were buried in a common grave. Despite this early setback, in the following years it seems that the pantomime African village became a regular feature of the international exhibition circuit, a modern extension of the carnival freakshow married to a colonialist ideology of European domination.

At this point the situation might seem clear. A naive Norwegian public are faced with an African other created by Belgian colonialism and presented as a carnival freakshow by an entrepreneur who knows how to create a sensation that will draw the crowds. And to self-consciously re-present this situation now, as Cuzner and Fadlabi plan to do, is both to point to historical Norwegian racism, and to ask what has changed since then, or even to suggest that some of these historical racist attitudes have survived.

This looks like an eminently reasonable conclusion, perfectly compatible with a contemporary liberal worldview, but it’s also a trap, constructed in part from the racist ideology that framed Singer’s own plans for a European Attraction. Looking more closely at the production of the Congolese Village, it is easier to see other political dimensions that might alter its contemporary interpretation.

Even from the very incomplete public records of the exhibition, two things stand out.

First, it seems that the Congolese Village was initially conceived as a Sami Village. In a Norwegian context, the Sami people are of course the proper colonial other, Norway’s unspoken conquest, and as such their representatives might well have have played the same uncomfortable role in the Oslo exhibition that the inhabitants of the Congo played in Brussels in 1897. But the exhibition committee rejected this idea on political grounds, since the Sami people, in the new settlement of Norwegian independence, were considered Norwegian citizens. «Tanken om at la stemmeberettigede norske borgere fremvises for penge er for usmakelig. Vi har derfor sløifet denne del.»

So already there is a political distinction made between the supposedly primitive lifestyles of Norwegian citizens, which cannot be displayed, and the supposedly primitive lifestyles of people from the Belgian Congo, which can.

Second, available sources indicate that the group who played the Congolese villagers in Oslo were a travelling troupe. They were not assembled specifically for the Norwegian centenary but were established performers on some kind of European circuit. Slavery having been abolished in Europe several decades earlier, it seems probable that some kind of symbolic contractual relationship existed between the performers and their management, which would have mandated some kind of recompense, most likely, but without evidence not necessarily, at an absolute minimum, for their services.

A third, and perhaps most important, consideration concerns the way in which the Congolese Village was established and represented. Though it seems that some small communication was possible across the language barrier, the form and means of the Congolese representation in Oslo was determined by the organisers of the exhibition. The villagers were not only on display, but on display within a set regime, obligated to play a passive role in which their interactions were tightly controlled. Though there is no record currently available of the contractual restrictions under which they appeared, the fact that contemporary reports only describe encounters within the Frogner Park exhibition suggests that their freedom of movement was restricted. And though this fact in itself does not constitute firm evidence, it seems altogether likely that, altough they were resident in Oslo for several months, the ‘Congolese Villagers’ were prevented from exploring the daily life of the city.

With these three adjustments to the initial image of the Congolese Village in mind, we can perhaps begin again to think about its significance now.

The power relationships at stake, even in 1914, were not only those of now-departed cultural prejudice or European imperialist oppression, but also the political and economic realities of emerging capitalist globalisation. What made Benno Singer’s Congo Village possible was not only the racism of its intended audience, but the formalisation of a decidedly unequal relationship within the structure of global capitalism. If not for the political intervention of the exhibition committee on the grounds of Norwegian citizenship, there might have been a Sami village on display in the 1914 exhibition. Similarly, it seems likely that the performers who did populate the Congo Village were what in the contemporary euphemism would be called economic migrants, their subjagation not a matter of pre-modern enslavement but a rational consequence of the socio-economic relationships established by force between European capital and African land and labour. The Congolese Village was a profitable attraction because of its perceived exoticism, presented in such a way as to manipulate the cultural attitudes of the Oslo audience. But its creation was also a consequence of the political rights of citizenship, or their absence, and the economic subjagation of a group of performers proletarianised by the imposition of capitalist social relations following their colonialist expropriation.

In other words, it seems possible to map significant elements of the material conditions that made the production of the Congolese Village possible directly onto current conditions in the global capitalist labour market. People dispossessed by the force of capitalist imperialism, people whose unchosen nationality does not give them the same rights accorded to, for example, Norwegian citizens, are remade as unrealised potential workers, impelled to leave homes and families and undertake precarious journeys in search of some imagined marginal economic benefit, which ultimately can be found only by accepting working conditions which deny them the basic human freedoms granted in full to those who take the profits from the enterprise.

With this reading in mind, the significance of Cuzner and Fadlabi’s project is both historical and absolutely contemporary, since it has the potential to once again address the same, unresolved and still modern questions of the political and economic rights of all people, including, but not limited to, those colonized and oppressed by the European adventures in Africa.

From What You Can’t Protect Yourself

Lars Cuzner’s project “From What You Can’t Protect Yourself” is a provocative and ongoing performative work that explores the complex dynamics of religious proselytization and belief systems. This project presents an intriguing paradox by featuring a non-believer engaging in the act of converting individuals to Christianity.

Conceptual Framework

The project operates within a conceptual framework that challenges traditional notions of religious conversion and authenticity. By having a non-believer as the proselytizer, Cuzner creates a tension between the message being conveyed and the messenger’s own lack of faith. This approach raises critical questions about the nature of belief, the power of persuasion, and the role of sincerity in religious discourse.

Performance as Critique

Cuzner’s work can be interpreted as a critique of religious evangelism and the mechanisms of conversion. By embodying the role of a proselytizer without genuine belief, the artist highlights the potential disconnect between the act of spreading religious doctrine and personal conviction. This performance serves to deconstruct the process of religious conversion, exposing its potential for manipulation and questioning the authenticity of religious experiences induced through external persuasion.

Ethical Considerations

The project inevitably raises ethical questions regarding the manipulation of individuals’ beliefs and the potential psychological impact on participants. By engaging in a performance that aims to convert people to Christianity while knowingly lacking genuine faith, Cuzner treads a fine line between artistic expression and ethical responsibility.

Context within Cuzner’s Oeuvre

“From What You Can’t Protect Yourself” aligns with Cuzner’s broader artistic practice, which often involves provocative and socially engaged works. This project shares thematic connections with his previous collaborations, such as the controversial “European Attraction Limited” (2014), co-created with Mohamed Ali Fadlabi, which recreated a historical human zoo to confront Norway’s colonial past.

Conclusion

Lars Cuzner’s “From What You Can’t Protect Yourself” stands as a challenging and thought-provoking exploration of faith, authenticity, and the power dynamics inherent in religious conversion. By positioning a non-believer as the agent of proselytization, the project invites critical reflection on the nature of belief systems and the complex interplay between personal conviction and external influence in shaping religious identities.

“We thought capitalism would create the conditions for perfect happiness by destroying every sense of belonging, by the nomadism of the rootless individual that results from the “deterritorialization” intrinsic to the development of the global economy. Now we have reached the apex of globalization and capitalist “deterritorialization,” and everything is returning: the Family, the nation state, religious fundamentalism. Everything is returning—but in a perverted, reactionary, conservative way, as the philosopher predicted.”

Christian Marazzi

Blind Carbon Copy presents 3 days of events Curators Go to The Bar

Participants: Joachim Hamou (DK), John W. Fail (EE/USA), Maria Arusoo (EE), Lars Cuzner (NO), Institut for Colour (NO), Maija Rudovska (LV) and Juste Kostikovaite (LT).

Curators: Juste Kostikovaite (LT) and Maija Rudovska (LV)

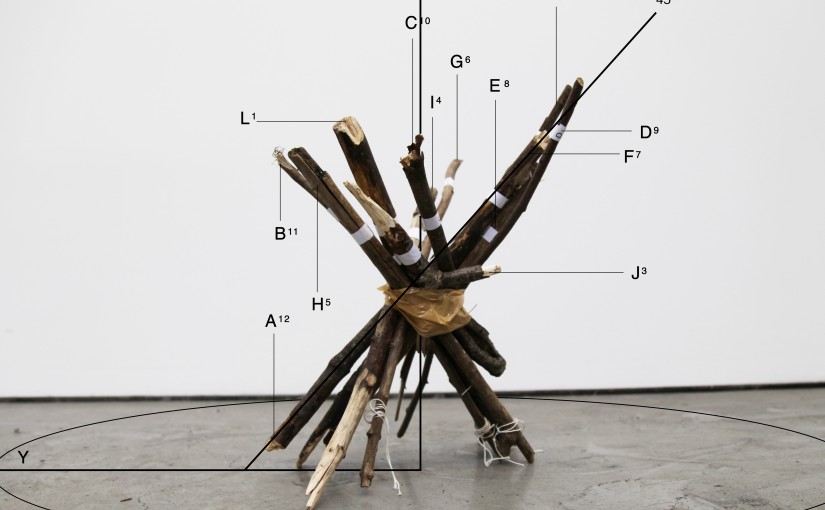

Sol LeWitt n’ shit

I’m sending you a box with everything you need to assemble my sculpture. It turns out I can’t send it assembled in the mail. It will just fall apart. The instructions that follow are as thorough as I could get them. Please send me photos of the process. We can also skype anytime. My skype name is larscuzner.

Before I get in to the installation process it will be of some use to know how the sticks are categorized.

[portfolio_slideshow id=1118]

Moses Harris, who discovered petrified wood, used the work of Isaac Newton to reveal the multitude of objects that can be created from three basic ones. (The ten commandments were, coincidentally, written on petrified wood, but that has nothing to do with this.) Moses was a naturalist who wished to understand the relationship between objects and how they are coded. He attempted to explain the principles of materiality and how further objects can be produced from three basics.

As much as his theory seems to simplify an argument for the purpose of fitting it in to an existing diagram, it does make some valid points. For one, there should have been twelve commandments, not ten, primarily because it makes more sense that three primary commandments times four stages of relations to the other commandments would allow for social life to develop in synchronicity with the natural world. Twelve is a superfactorial, being the product of the first three factorials.

Instructions for installation:

1. Place the sticks on the floor exactly as shown in the image below.

2. Put your hands on either side of the sticks with your left hand at A12 and your right hand at L1.

3. Anchor your right fingertips just below what will be the centre of gravity for the standing sculpture.

4. Your right hand should be curled into a backwards C. Do not curl your left hand.

Now you will plot the x-axis.

5. Drag your left hand towards your right hand while slowly letting your right hand push the bottom of the sticks towards the centre of the X-axis.

Make sure A12 and L1 enter X-axis as headers.

6. Drop your right hand slowly towards you as the sticks gather in you cupped hand.

(B11 and K2 should almost stick to the headers.)

6. Anchor your left fingertips on the floor directly below the centre of gravity.

7. With your right hand cupping the sticks, but the bottoms of the sticks against your left fingertips.

8. Curl your left hand into a C with the fingertips anchored.

9. Move your right hand up towards the centre while simultaneously sliding your left hand up, with the centre of your palm towards the centre of gravity. Don’t worry about how the sticks move now, just make sure the middle finger on your right hand meets the middle finger on the left and that your thumbs meet up in the same way.

10. You should now be holding the sticks in the centre of gravity, just below the centre point, between your fingers, which form a circle.

11. Ask your assistant for a 7 3/4 inch piece of packing tape (included in the box).

12. Ask your assistant to place one end of the tape directly under the protruding branch of J3 (this will be just above the thenar space of your right hand, the area with webbing between the thumb and index finger) and wrap it counter clockwise along the horizontal axis.

The equation for a rotational transformation (in counter clockwise

direction) is x’ = xCos(A12) – ySin(A12)

So now, A12 should be the only stick on a perfect 45º angle, point to point, without touching the floor. Both A12 and L1 will be off the floor. The tripod touching the floor taking the weight of the sculpture should consist of – H6 (running parallel with L1and crossing A12), F7 (running parallel with A12 and crossing L1) and I4 crossing both A12 and L1. Everything else should fall into place accordingly, but double check. It should be right, even if it is rotated. Any use?

All this might be a bit esoteric so if you want to skype that’s OK with me.

Done. Use the image as reference.

I really hope you want to put this work in the show. I love your work. Did you know that to conserve metal during World War II, Oscar statuettes were not made out of wood as many think, they were made out of plaster. The only Oscar statuette ever made of wood was presented to the ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his dummy Charlie McCarthy in 1938. Before Edgar’s dotter, Candice Bergen, had established a public identity of her own she was often referred to as Charlie McCarthy’s sister. But it was difficult for Candice to be the sister to a piece of wood. It was hard to make sense of because you knew he wasn’t real and yet he was treated like a living bigger brother, he had his own room, got presents on his birthday and so on. It was sometimes painful for her, because she felt she had to compete with this puppet for her father’s love and she resented it.

Ventriloquism entails the effacement of the speaker while the speaker pretends to listen. It’s not an issue of who gets to represent whom and to what end, but what our role is in its construction of what we are willing to believe, internalized self-deception or externalized self-plagiarism.

The Mormon Church still uses the Quorum of the Twelve and receives revelations from its prophets; it’s a highly secretive process. The famous prophet, Wilford Woodruff, is well known for having received the revelation that prohibited plural marriage, mind you, at the time when the government was penalising the church for practicing polygamy.

In 1913 Woodrow Wilson became the 28th president of the United States. It was a common misconception that Woodrow Wilson and Wilford Woodruff were the same person. Many Mormon children grew up thinking that the U.S. once had a prophet as a president, which isn’t true.

This children’s song was written to help clarify the issue.

our latter-day prophets are number 1, Joseph Smith, then Brigham Young, John Taylor came 3rd we know, then Wilford Woodruff, Lorenzo Snow, Joseph F. Smith, remember the F. , Heber J grant, then George Albert Smith, David OOOO Mccay was followed by Joseph Fielding Smith, then Harold B. Lee, Spencer W. Kimball, Ezra Taft Benson, Howard W. Hunter, Gordon B. Hinckley LED THE WAY, “WE HEAD AND FOLLOW PRESIDENT MONSONS WORDS TODAY” (you need to sing that last part kind of fast because new prophets get added to the song. Right now I think it’s kind of out of synch.)

In 1919 Woodrow Wilson suffered a stroke, His wife, Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, spoke on his behalf as he sat alongside. But people didn’t buy that Woodrow was the one speaking. Edith was called “the secret president” or “the first female president”.

You can still get Moses Wood apples named after Sgt Moses Wood who died in 1915 in Wilson’s war.

Don’t hesitate to call or skype or anything if you run into problems.

Sincerely

Lars Cuzner

Broadcast through a Brother

At the top of his career, from 1936 to 1956, Edgar Bergen, a celebrated ventriloquist, performed with his magnetic dummy Charlie McCarthy, on radio. His illusory talent for appearing not to be speaking while speaking captured an audience that could not see him.

[portfolio_slideshow id=12]

Bergen, the son of Swedish immigrants in Chicago, taught himself ventriloquism at the age of 11. As a teenager he was working at a silent movie theatre and giving performances at a nearby church. Lars and Steven Cuzner, as children in Sweden, grew up listening to recordings of Bergen. They would take turns to practice channeling two voices from a single source, alternating between using the other brother as the dummy. Thereby projecting themselves outside of the self and entering the other’s body, the other’s character. Broadcast through a Brother is the speech of a figure that has manifested over time in suspended ventriloquism throughout their lives, allowing one brother to imagine what the other is prepared to do, or say. Today they share an encoded relationship that is preset with cues, not only to what the other might say, but also to the tone and the style of its delivery.

Video documentation from Based in berlin. link Vimeo

Link: based in Berlin

Recurring Individual Conversations

Fully confidential, one-to-one conversations, teetering four meters above the gallery floor, at UKS. Six participants signed up for conversations once a week for a full year. The conversations were not documented.

Lars Cuzner’s project “Recurring Individual Conversations” at UKS (Unge Kunstneres Samfund) in Oslo in 2010 was a year-long performative installation that explored the boundaries of intimacy, trust, and artistic engagement. The project consisted of Cuzner offering confidential, one-on-one conversations with participants while positioned four meters above the gallery floor.

Clearly within the context of relational aesthetics and participatory art practices, it served a unique spatial and temporal environment for interpersonal exchange, Cuzner challenged traditional notions of artistic production and exhibition.

Six participants committed to weekly conversations over the course of a year. The elevated position of the artist during these interactions introduced an element of physical precarity, potentially serving as a metaphor for the vulnerability inherent in intimate dialogue. The project emphasized the importance of trust in artistic encounters, with Cuzner guaranteeing full confidentiality to participants. By extending the project over a full year, Cuzner explored the potential for long-term artistic engagement and the development of relationships over time.

The box ended up staying there for 4 years cuz it was too fucking expensive to take down. It became a part of every show at UKS. I saw some documentation though, from some shows, that had photoshopped out the box.

Since everyone who participated in the project signed a confidentiality agreement (a contract which of course was destroyed after signing), it was difficult for critics to attain any real content information about the going-ons in the box. Art critic, Kjetil Røed, did however write a 60 page essay, “Lars Cuzner’s Conversational Ghosts”, which can only be described as bitter character assassination of me. Luckily no one seems willing to publish this piece of slanderous garbage.

The piece was quietly commenced April 16, 2010 during the Oslo Speculations seminar at UKS, and ended April 16, 2011 without ceremony.

Four years later, finally, an artist demanded the removal of the box for his show in February 2014. Here is a text and first documentation without the box “Plutselig utslett” by Line Ulekleiv.

Participants in project:

Per Platou, Client, Artist and curator. Co-ordinator for PNEK

Victoria Stewart, Client, Psychologist

Serina Erfjord, Client, Artist

Suzana Martins, Client, Program co-ordinator for 0047

Magnus Oledal, Client, Artist

Anna Ring, Client, Artist

Bed Bug Formication

A single session night class about the extermination of imaginary bed bugs.

Thought to have been almost extinct for almost half a century, Norway is now starting to realize the effects of mass habitat migration.

Thought to have been almost extinct for almost half a century, Norway is now starting to realize the effects of mass habitat migration.

Ekbom syndrome, and delusions of parasitosis is a strong delusional belief that you are infested with parasites, whereas in reality no such parasites are present.

Formication is the medical term for a sensation that resembles that of insects crawling on (or under) the skin. More rarely, susceptible individuals who fixate on the sensation may develop delusional parasitosis, becoming convinced that this sensation is being caused by actual insects, despite repeated reassurances from physicians, pest control experts, and entomologists.

The control freak knows that the cure is homeopathic. An abnormal need to control is controlled with more control, something the control freak should be very good at, but isn’t. There is still a great deal of confusion about how the disorder should be classified.

Non-profit initiative for performance art and art in the social.

Waste your time. It’s over.

Original score. Leif Cuzner.

Camera. David Spriggs.